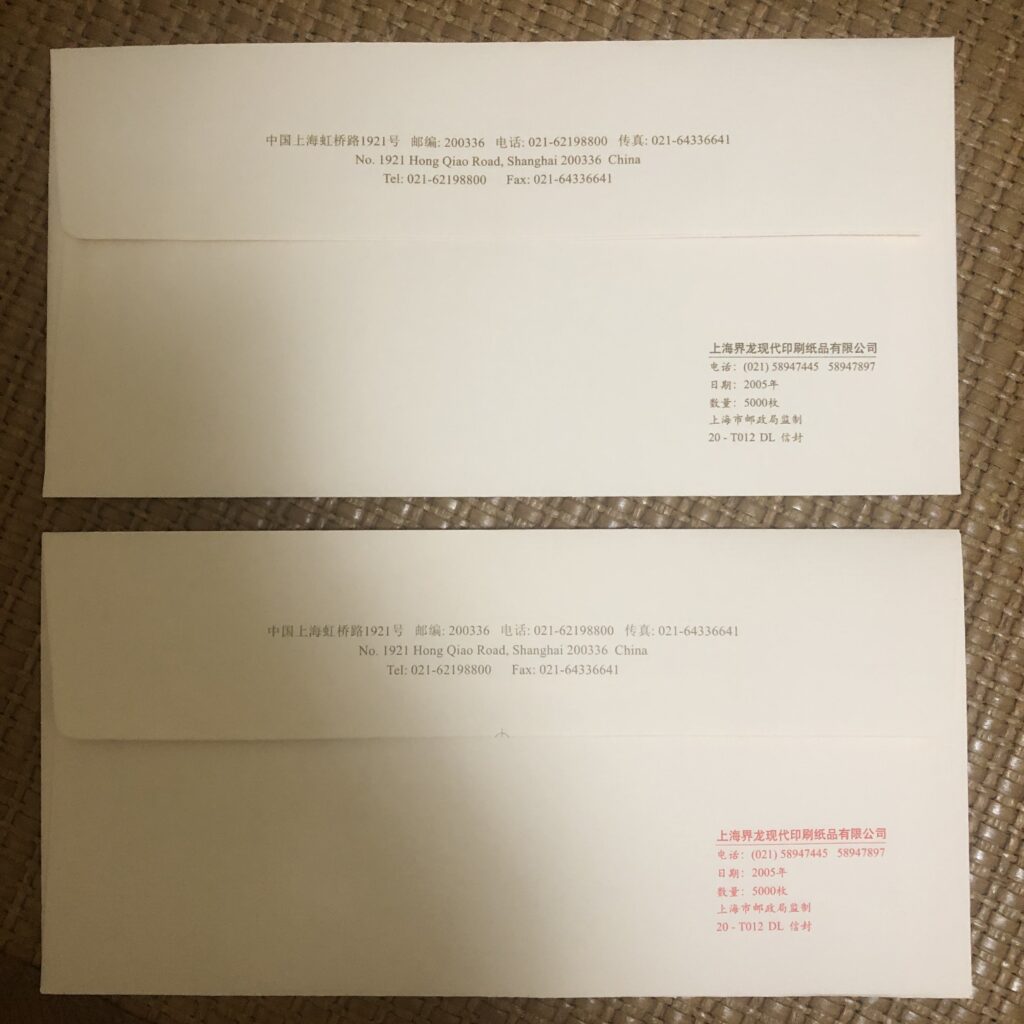

Apologies in advance for this post having nothing to do with a post office. Anyway(s), I was at Xijiao State Guest Hotel last night, and found in my room’s drawers some envelopes preprinted with the hotel’s name, address and logo. Such envelopes, specifically designed for major institutions and other “units (danwei)” — an umbrella term which may be used to refer to any company, organization or entity — are indeed not uncommon in China and elsewhere, but these ones are of some greater interest than others given the prominence of their issuer. It is also the first time that I saw a “Par Avion” tag in Chinese.

As for the Hotel itself (which I insist should be translated not as Xijiao State Guest Hotel but either Xijiao State Hotel or Xijiao State Guest House, but I digress), ample information may be found on the Chinese internet, so an executive summary should suffice — in 1946 Yao Naizhi, heir to a Shanghai industrial fortune, built on these acres a modern country house modeled after Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, and which was called at the time, somewhat unceremoniously, “Yao’s Curiosity (Yaoshi guaiwu, lit. ‘Yao’s weird house’).” After the People’s Republic came into being and in the early 1950s, industrialists (or “capitalists” if you are so inclined) like Yao lived pretty much their same old lifestyle, but in the mid-1950s (a more specific date evades me) he traveled to Taiwan, allegedly said something rather careless, and was promptly deemed a counter-revolutionary. Yao himself fled to the United States, but his extended family in Shanghai was understandably concerned with their prospects.

It so happens that the municipal leadership of that city was looking for a suitable place to accommodate Chairman Mao Zedong for his frequent visits there. His former local residence was reportedly quite commodious and prone to snake attacks (I kid you not), and the Yao family, having somehow heard of such news, donated his Curiosity to the municipal government, which gladly accepted and immediately proceeded to expand the complex for housing Mao’s retinue. And so it became Shanghai’s primary hotel for party leadership, other government officials, and foreign dignitaries, and witnessed such historic moments as signing of the Shanghai Communique in 1972, which initiated the long overdue normalization of diplomatic relations between China and the U.S. During China’s economic reform the Hotel began to serve patrons who fall into none of the three aforementioned categories, was remodeled in 2001, and now functions as an upscale (but in no way exclusive) recreational complex with gardens (where lives a pair of peacocks), artificial waterways, a spacious convention center and a sports center featuring some surprisingly liminal spaces.